Federal Circuit Review – Reviewed (At Sporadic Intervals): Second Edition, by Bill Burgess

The D.C. Circuit clearly has an outsized role in the development of administrative law. But it’s hardly the only court of appeals deciding important administrative law cases. Other people have posted to highlight the Fifth and Ninth Circuits’ contributions. This post is to make three points about why the Federal Circuit may have the strongest claim of any court of appeals not housed on Constitution Avenue to the attention of administrative scholars and practitioners.

1. The Federal Circuit’s jurisdiction has been primarily administrative, non-patent cases, since the beginning. Prof. Rochelle Dreyfuss’s 1989 article is probably the best comprehensive account of where the Federal Circuit came from. Congress created the Federal Circuit in 1982, mainly to bring uniformity to patent law and to alleviate forum-shopping by taking appeals from district court patent cases out of the twelve regional circuits and channeling them all to a single appellate court. But, to keep the Federal Circuit from becoming too specialized or isolated, Congress also gave the new court exclusive jurisdiction over appeals from a variety of administrative bodies and Article I courts. Most of these other pockets of Federal Circuit jurisdiction are listed in the subsections of 28 U.S.C. § 1295(a).

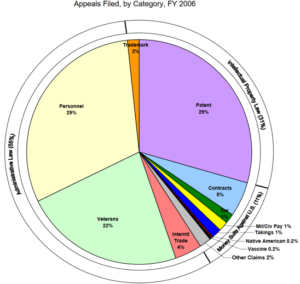

The D.C. Circuit has its familiar alphabet soup of agencies like the EPA, FCC, FERC, and FLRA. But the Federal Circuit has its own alphabet soup of agencies it reviews, like the ITC, MSPB, OPM, GAO-PAB, PTO, OOC, PTAB, and TTAB, among others. As the chart below shows, in 2006, 55% of the appeals filed in the Federal Circuit were administrative appeals from agencies other than the Patent and Trademark Office.

The appeals the Federal Circuit hears from these agencies are interesting and varied. Trade cases can often present questions of Chevron and Seminole Rock/Auer deference. Veterans cases have required the court to consider things like the scope of Chenery’’s harmless error exception.

The Federal Circuit’s administrative law decisions have also led to some of the more important cases from the Supreme Court. A Federal Circuit trade case led to United States v. Mead Corp., 533 U.S. 218 (2001). A Federal Circuit appeal from the Patent and Trademark Office led to Dickinson v. Zurko, 527 U.S. 150 (1999), the main modern case on APA review of agency fact finding. And of course, after years of speculation about whether Seminole Rock/Auer deference was long for this world, the Supreme Court confronted that doctrine directly by reviewing a Federal Circuit veterans benefits case, and giving us Kisor deference. Why did the Supreme Court choose Kisor rather than any of the other cases the Supreme Court bar offered up in cert petitions? Only the Justices know for sure, but Judge O’Malley’s dissenting opinion in the Kisor Federal Circuit case suggested that Kisor might have been a uniquely suitable vehicle to consider the limits of Seminole Rock/Auer deference because of the tension between that doctrine and Supreme Court precedent holding that veterans-benefit statutes should be construed liberally in favor of veterans. In other words, Seminole Rock/Auer put a thumb on the agency’s side of the scale, but veterans-law-specific Supreme Court precedent put a thumb on the other side of the scale.

2. The Federal Circuit’s New Administrative Patent Appeals Are Uniquely Important. The Federal Circuit’s administrative docket has always been important, but has become much more so in the past few years. As I explained a bit more in an earlier post (which, in retrospect, might be the inaugural edition of “Federal Circuit Review — Reviewed”), in 2011 Congress gave the Patent Office new rulemaking power and created new adjudicative proceedings at the Patent Office before panels of “administrative patent judges.” In part because of the high financial stakes patent cases can present, some of these cases are exceptionally well-lawyered and present complex administrative law issues. In these new proceedings, a company will often petition the Patent Office to revoke a patent because that company is being sued in district court for infringing that patent and faces a potential injunction or nine-figure damage award. The Federal Circuit’s five separate opinions in its en banc decision in Aqua Products, Inc. v. Matal, 872 F.3d 1290 (Fed. Cir. 2017), together manage to cite most of the greatest hits of Supreme Court administrative law jurisprudence as eleven judges wrestle with the Patent Office’s treatment of burdens of proof in the new administrative proceedings Congress created.

The current pie chart of the Federal Circuit’s caseload is below. The large orange slice is direct appeals from the Patent and Trademark Office, which include these new administrative proceedings.

Some of the newest criticisms of Chevron from the Supreme Court have come, not from the D.C. Circuit’s decisions reviewing the work of the EPA or FCC, but from Federal Circuit administrative patent cases. It was in Cuozzo Speed Technologies, a patent case, that Justice Thomas concurred to urge the Court to confront “Chevron’s fiction that an ambiguity in a statutory term is best construed as an implicit delegation of power to an administrative agency to determine the bounds of the law.” And SAS Institute Inc. v. Iancu, another patent case, produced the apparent warning shot that “whether Chevron should remain is a question we may leave for another day.” Beginning with OT 2015, the Supreme Court has regularly reviewed cases from Federal Circuit’s new docket of administrative patent appeals, e.g., in Cuozzo, SAS Institute, Return Mail, Oil States, and most recently in Dex Media Inc. v. Click-to-Call Technologies (pending). In other words, these cases have the Supreme Court’s attention for the foreseeable future.

3. The Federal Circuit’s District Court Patent Cases Are Administrative Law Cases Too. Finally, perhaps at the risk of defying “the ancient wisdom that calling a thing by a name does not make it so,” the Federal Circuit’s district court patent appeals can also plausibly be called administrative law cases. By that, I don’t just mean that lawyers litigating district court patent cases need to understand agency practice. (They do, though. Most every patent infringement case involves disputes over the meaning of parts of the administrative record that led to the patent issuing in the first place. Anyone who litigates a pharmaceutical patent case needs to understand FDA’s role in approving branded and generic drugs. And woe to the patent litigator who hopes to practice for very long without knowing what the MPEP is.). I mean something more fundamental than that.

A patent is a property right against the public, issued by a federal agency. In nearly every patent infringement case, the defendant raises the defense that the patent is invalid—i.e., the Patent Office was wrong to issue it in the first place. (See 35 U.S.C. § 282(b).). This means that in nearly every patent case, the fact finder is passing directly on the validity of agency action. Indeed, as Prof. John Duffy has explained in a recent article, the district court patent cases across the country may be described as “the branch of administrative law involving one of the oldest surviving federal agencies,” in which “juries are routinely and explicitly called upon to pass on the ‘validity’ of federal administrative action.” Professor Duffy’s article goes on to explain that this practice is not an isolated anomaly, and that it connects the modern world to a practice that was more common in the nineteenth century and that provides insights about legal history and “reveals a deep connection between administrative law and the traditions of criminal procedure.” You should read the whole thing if you have time, but my point for purposes of this post is that almost 100% of the Federal Circuit’s docket might plausibly be called “administrative law.” Unlike the D.C. Circuit or the regional circuits, the Federal Circuit has no criminal jurisdiction and no diversity jurisdiction. Rather, its docket is a wide variety of appeals that could plausibly be described as all administrative law, all the time. The Supreme Court is paying close attention, and if you care about administrative law, you should too.

Bill Burgess is a partner in the Washington, D.C. office of Kirkland & Ellis LLP.