Fifth Circuit Review – Reviewed: New Look, Same Great Taste!

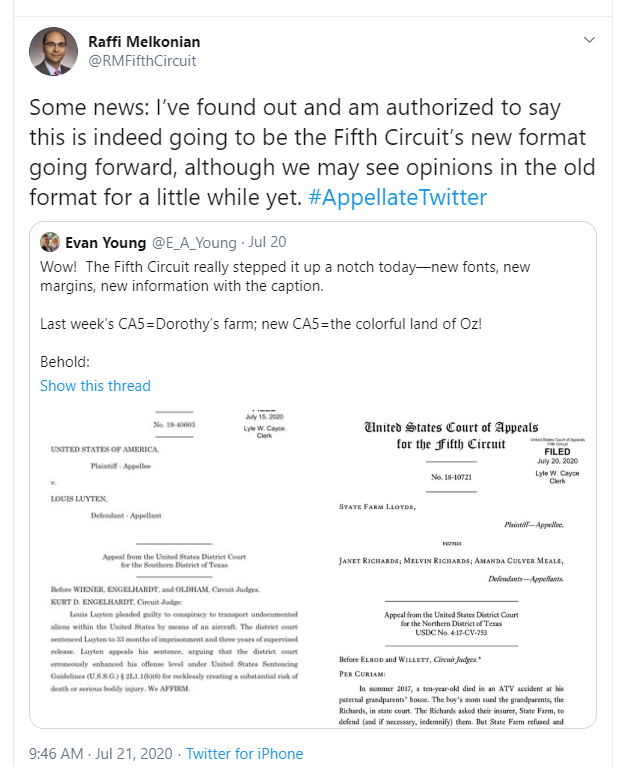

Welcome to another installment of Fifth Circuit Review – Reviewed. Earlier this month, the Fifth Circuit shocked the world. My former (and totally amazing) boss, Evan A. Young, summed up the historic moment:

In need of guidance, #AppellateTwitter looked to their fearless leader, Raffi “@RMFifthCircuit” Melkonian, who soon delivered the official confirmation:

Not everyone was ready for such dramatic change:

Some were overwhelmed by the pandemonium:

Others had mixed feelings:

While not everyone is in love with the formatting changes, most are coming around. When it comes to fonts, I’ve always been partial to Georgia and Century Schoolbook, but I must admit, the Fifth Circuit’s choice–Equity–is growing on me already.

Anyway, enough with all that. Let’s get into some administrative-law decisions, shall we?

The Fifth and Tenth Circuits Diverge on Title V Permitting Under the CAA

Environmental Integrity Project v. EPA, No. 18-60384 (Haynes, Graves, Duncan)

Title V of the Clean Air Act requires certain pollution sources to obtain operating permits. 42 U.S.C. § 7661b. The permit must include enforceable emissions standards and other conditions as “necessary to assure compliance with the Clean Air Act’s applicable requirements” for air pollution prevention and control. Id. § 7661c(a). The statute doesn’t define the term “applicable requirements,” however, so EPA defined it by regulation to include the terms and conditions of Title I preconstruction permits, which operators must obtain before construction or modification of certain sources. 40 C.F.R. § 70.2.

Seeking to expand its Baytown, Texas plant, ExxonMobil requested a revised permit under Title V. When EPA didn’t object to ExxonMobil’s proposed revision, Petitioners Environmental Integrity Project and Sierra Club petitioned EPA to object, see 42 U.S.C. § 7661d(b)(2), arguing that ExxonMobil’s underlying Title I permit for the expansion was invalid.

EPA rejected Petitioners’ arguments and declined to object. In so doing, EPA relied on the “Hunter Order.” See In the Matter of PacifiCorp Energy, Hunter Power Plant, Order on Petition No. VIII-2016-4, (Oct. 16, 2017). There EPA denied a petition to object to a Title V permit for a Utah power plant, explaining that it construes 40 C.F.R. § 70.2 to make the requirements of the operator’s underlying Title I permit the “applicable requirements” for purposes of Title V permitting “without further review.” As a result, EPA explained, a petition to object to a Title V permit is not a viable avenue for challenging the validity of the operator’s underlying Title I permits.

The Hunter Order marked EPA’s return to its original interpretation of § 70.2 shortly after Title V’s enactment in 1990. In the interim, EPA had abandoned that construction in favor of a broader reading of § 70.2 that permitted the agency to examine the validity of the permitting decisions underlying the operator’s related Title I permit.

Despite the fact that the Hunter Order and EPA’s order in this case both claimed to interpret EPA’s implementing regulation, 40 C.F.R. § 70.2—and not Title V of the Clean Air Act—the government defended it before the Fifth Circuit as a permissible interpretation of ambiguous statutory language, namely 42 U.S.C. § 7661c(a). Interestingly, while this case was pending, the same government lawyers were busy defending the Hunter Order in another case pending before the Tenth Circuit. See Sierra Club v. EPA, No. 18-9507 (10th Cir.). There, however, the government defended the Hunter Order not as a permissible interpretation of ambiguous statutory language entitled to Chevron deference but as a permissible interpretation of the regulation entitled to Kisor deference.

So, to sum up, we have an EPA order that purports to announce a return to an old interpretation of a regulation. When that order is challenged in the Tenth Circuit, the government invokes Kisor in defending EPA’s view. Yet when that same interpretation is challenged in the Fifth Circuit, the government takes a different tack, resting its entire defense of EPA’s interpretation on Chevron. Pretend you’re a Fifth Circuit judge assigned to this panel. Do you:

- Go along with the government’s invocation of Chevron and simply apply the familiar two-step framework to the Hunter Order’s interpretation of a regulation?

- Reject the government’s attempt to invoke Chevron explaining that Chevron doesn’t apply to agency interpretations of regulations and apply Kisor or Skidmore instead? Or

- Reject the government’s attempt to invoke Chevron explaining that (a) Chenery I demands that the agency’s interpretation be upheld, if at all, for the reasons the agency gave when it announced the interpretation; (b) EPA in both the Hunter Order and the Order denying the petition to object in this case purported to justify its new interpretation as a permissible construction of its own regulation—not of the statute; and therefore (c) Chenery I requires the Court to uphold the agency’s interpretation only if it constitutes a permissible reading of a genuinely ambiguous regulation?

The Fifth Circuit’s answer? None of the above:

I’ll admit I didn’t know courts could avoid addressing Chevron’s applicability altogether when the appropriate level of deference is unclear. In any case, why do you suppose the panel concluded that the appropriate level of deference under Chevron was unclear? As far as I can tell, the opinion itself never answers that question.

The Court does clarify that while “[t]he Hunter Order is framed largely as an interpretation of 40 C.F.R. § 70.2,” it “[n]onetheless … analyze[d] [it] as a construction not only of § 70.2 but also of Title V and the Act as a whole.” In my view, that approach arguably raises the Chenery I problem I alluded to above—i.e., blessing the Hunter Order (and the EPA Order at issue in this case) for reasons other than those EPA itself gave in support of the Orders when it issued them.

In any event, the panel goes on to explain that it finds the government’s defense of EPA’s interpretation persuasive and therefore entitled to Skidmore deference even though the agency’s current interpretation is not “consisten[t] with [its] earlier … pronouncements” on the subject. (quoting Skidmore v. Swift & Co., 323 U.S. 134, 140 (1944)).

On July 2nd, however, the Tenth Circuit reached the opposite conclusion in Sierra Club v. EPA, rejecting EPA’s interpretation of 40 C.F.R. § 70.2 as incompatible with the unambiguous language of the regulation. As a result, the Court vacated the Hunter Order. Along the way, the Tenth Circuit addressed the Fifth Circuit’s opinion at some length. The panel flagged the Chenery I issue I’ve discussed here before vacating the very EPA policy that the Fifth Circuit’s opinion had just upheld. In the end, though, the Tenth Circuit emphasized that because it held only that the regulation precluded EPA’s interpretation, it didn’t “need [to] reach the statutory issue underlying the Fifth Circuit’s recent opinion.”

That’s all well in good. If you ask me, though, the conflict is undeniable. The courts reach opposite conclusions about the validity of the same EPA policy. They address different defenses of that policy not because they secretly agree with each other but because the government pursued inconsistent litigation strategies in the otherwise-parallel cases. What are the chances those strategic choices were unintentional? And if they were intentional, what do you think explains the government’s inconsistent approaches?

Petitioners in the Fifth Circuit case have filed a petition for panel rehearing. I would keep a very close eye on this one. Despite the Tenth Circuit’s attempt to downplay the conflict, I wouldn’t be surprised if this issue ends up in front of the Supreme Court before it’s all over.

Administrative Law at Houston’s Downtown Aquarium

Next we have Houston Aquarium, Inc. v. OSHRC, No. 19-60245 (5th Cir. July 15, 2020) (Barksdale, Higginson, Duncan), a case about H-Town’s Downtown Aquarium—a place that’s ridiculous or ridiculously awesome depending on who you ask. The Aquarium’s website gives visitors some sense of what they’re in for:

Downtown Aquarium is the product of redeveloping two downtown Houston landmarks – Fire Station No. 1 and the Central Waterworks Building. This magnificent six-acre entertainment and dining complex is a 500,000-gallon aquatic wonderland, home to over 300 species of aquatic life from around the globe. With a full-service restaurant, an upscale bar, a fully equipped ballroom, aquatic & geographic exhibits, shopping and a variety of amusements, Downtown Aquarium has it all!

Not hooked yet? What if I told you the place is also home to several white tigers? Why? Well, if you’re asking, you’re obviously not Mike Tyson or any of the 12,825 Houstonians and H-town visitors who have given the Aquarium an average 4.1/5 stars on Google Reviews.

Anyway, this case isn’t about the tigers, though they have certainly been the subject of plenty of litigation. This case is about the many divers the Aquarium employs to feed the animals and clean the tanks. Back in 2011, an Aquarium employee complained that some of the dives taking place at the Aquarium were not scientific. If true, that would mean the Aquarium was violating OSHA’s Commercial Diving Operations regulations. An ALJ agreed, and a divided OSHRC panel affirmed.

The Fifth Circuit reversed, holding that “[u]nder a plain reading of [29 C.F.R. § 1910.402], as well as the regulation guidelines and regulatory history, these dives do qualify as scientific diving.” Judge Higginson’s opinion for a unanimous panel doesn’t discuss deference doctrines because the Court’s holding was based entirely on a plain-language analysis supplemented with a painstaking disquisition on the regulations broader structure and history.

Fifth Circuit Prohibits Injunctive Relief Against the SBA; Another Federal Court Disagrees

In In re Hidalgo Cty. Emergency Serv. Found. v. Carranza, No. 20-40368 (5th Cir. June 22, 2020) (Smith, Higginson, Engelhardt), the Fifth Circuitheld that an injunction against the SBA related to the exclusion of bankruptcy debtors from receiving PPP funds under the CARES Act was improper. In a unanimous opinion authored by Judge Smith, the Court explained that the injunction ran afoul of Fifth Circuit precedent holding that all injunctive relief against the SBA is absolutely prohibited. See Teague v. City of Flower Mound, 179 F.3d 377, 383 (5th Cir. 1999). Within a week’s time, however, the U.S. District Court for the District of Maryland had expressly rejected the Fifth Circuit’s approach. See Defy Ventures, Inc. v. U.S. Small Bus. Admin., No. CV CCB-20-1736, 2020 WL 3546873, at *6 (D. Md. June 29, 2020).

Fifth Circuit Rejects Non-Delegation Claim

Judge Smith also wrote for a unanimous panel in Big Time Vapes, Inc. v. FDA, No. 19-60921 (5th Cir. June 25, 2020) (Smith, Higginson, Engelhardt), rejecting a non-delegation challenge to the constitutionality of Congress’s provision of authority to FDA to decide which “tobacco products” are subject to the Tobacco Control Act’s “thorough [regulatory] framework.” After distinguishing Panama Refining Co. v. Ryan, 293 U.S. 388, 433 (1935) and A.L.A. Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States, 295 U.S. 495, 542 (1935), the Court concluded:

The Court might well decide—perhaps soon—to reexamine or revive the nondelegation doctrine. But “[w]e are not supposed to … read tea leaves to predict where it might end up.” United States v. Mecham, 950 F.3d 257, 265 (5th Cir. 2020), cert. denied,––– U.S. ––––, 2020 WL 3405899 (U.S. June 22, 2020) (No. 19-7865). The judgment of dismissal is therefore AFFIRMED.

Fifth Circuit Defers to HHS’s Interpretation of Medicaid Act Under Chevron

In Baptist-Memorial Hospital v. Azar, 956 F.3d 689 (5th Cir. Apr. 20, 2019) (Higginbotham, Dennis, Ho), the Fifth Circuit joined three other circuits in holding HHS’s Final Rule clarifying that for purposes of calculating hospitals’ “disproportionate share hospital” (DSH) compensation, a hospital’s “costs incurred” are net of payments to third parties like Medicare and private insurers embodied a a construction of the Medicaid Act that was permissible and therefore entitled to Chevron deference. See Medicaid Program; Disproportionate Share Hospital Payments—Treatment of Third Party Payers in Calculating Uncompensated Care Costs, 82 Fed. Reg. 16,114 (2017). More here.

More on these and other administrative law decisions from the Fifth Circuit is available here.