The Rise of Hill Staffers-Turned-Regulatory Commissioners, by Brian D. Feinstein

This post draws on joint work with M. Todd Henderson, entitled Congress’s Commissioners and published in the current issue of the Yale Journal on Regulation.

If recent history is any guide, senators considering executive-branch nominations in the coming months likely will see some familiar faces at witness tables. Currently, nearly half of all commissioners and board members on eleven major multi-member agencies served as congressional staffers earlier in their careers.

Yet the placement of former Hill staffers on independent regulatory commissions is a relatively recent phenomenon. In Congress’s Commissioners, M. Todd Henderson and I show how the practice complicates our understanding of both Congress and administrative agencies. Concerning the former, the presence of so many Hill alums on commission daises challenges the standard account of a Congress in decline. Regarding the latter, staffers-turned-commissioners may dramatically alter the functioning of the administrative state by importing Congress’s culture into agencies.

To study the staffers-turned-commissioners phenomenon, we leverage data on the professional backgrounds of almost one-thousand commissioners on eleven major commissions for the entirety of each commission’s existence. (Political scientist David Nixon collected these data through 2000; we updated his dataset through 2018.)

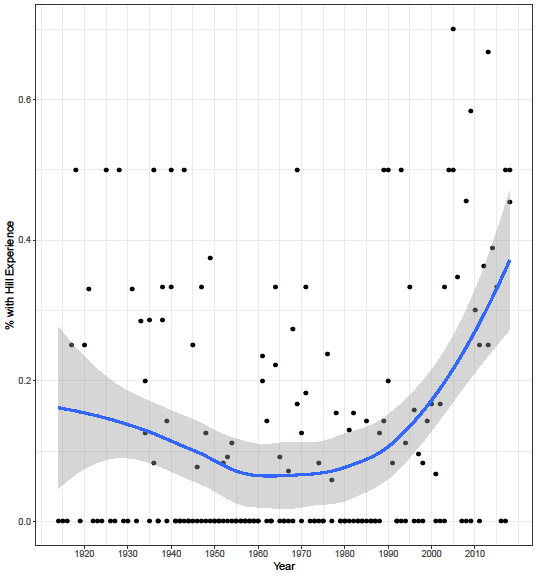

What we found surprised us: the practice of appointing former Hill staffers as commissioners is a relatively recent phenomenon. Each dot in the following figure indicates the proportion of commissioners will Hill experience that were appointed in a given year. The figure displays a trend line in blue, along with associated 95 percent confidence intervals in gray.

Proportion of New Commissioners with Hill Experience

The figure reveals an overall slight decrease in the proportion of staffers-turned-commissioners from the New Deal era to the 1980s. The trend turns positive in the 1980s, and accelerates in the mid-2000s. Empirical analysis shows a handful of outlier agencies or the presence of divided government (a more frequent occurrence in recent decades) are not driving these results. Further, although the trend accelerates around 2005, neither is a discontinuity around that year generating these results. Instead, it is quite simply a time trend: since around 1980, the proportion of former congressional staffers serving on independent regulatory agencies has increased almost fourfold.

Faced with a diminished direct role in policymaking due to legislative gridlock and presidential aggrandizement, senators may have turned to emphasizing the appointment of their branch’s personnel to head regulatory agencies as an alternative means of influence. That practice offers several advantages to legislators. For one, lawmakers can gauge their staffers’ ideological commitments through frequent, in-person interactions. Staffers-turned-commissioners also may be more pliable to congressional demands. That Hill staffers were acculturated to an institution that values loyalty to one’s political principal and party may make them particularly attractive as appointees.

In short, placing loyal aides onto commissions may enable lawmakers to indirectly influence policy. That this practice took off roughly contemporaneously to growth in presidential involvement in agency decision-making suggests that Congress has turned to one of its core, non-delegable functions—the Senate’s role in appointments—to counter, in part, the president’s heightened role in administration.

The presence of staffers-turned-commissioners has significant consequences for administrative agencies. A large and varied literature finds that earlier work experiences shape individuals’ later professional behavior through the transmission of workplace culture. For Hill staffers, that workplace is increasingly characterized by polarization, adversarial relations, and dysfunction. Like Johnny Appleseeds, staffers-turned-commissioners then bring Congress’s ways with them into the administrative state.

For instance, a 2011 inspector-general report charged that Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) Chair Gregory Jaczko failed to inform his fellow commissioners of budgetary changes and engaged in other hardball tactics in an effort to conceal his efforts to stop work on the Yucca Mountain, Nevada, nuclear waste storage facility. Other commissioners wrote to the White House to express their “grave concerns” with Jaczko and allege that he “intimidated and bullied senior career staff [and] … created a high level of fear and anxiety resulting in a chilled work environment.”

Prior to Jaczko’s appointment to the NRC, he served as appropriations director and science policy advisor to Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-NV), who opposed the Yucca Mountain site. President Obama appointed Jaczko to the NRC at Senator Reid’s urging. Given his biography, his aggressive pursuit of his political patron’s objectives is unsurprising.

Or consider the SEC. A 2013 New York Times article reported that the SEC “has in recent years splintered into factions far more than ever before.” Then-SEC Chair Arthur Levitt laid the blame largely on staffers-turned-commissioners, observing that they “tend to embrace the philosophy of their mentors.”

Our conversations with senior SEC officials are consistent with Levitt’s account. The following observations, each from a different senior SEC official, are illustrative:

- “There are things that we could be doing today—easy wins on policies that reasonable people on both sides would agree to—but we aren’t doing them because commissioners are not here to compromise but are just doing the bidding of their congressional masters.”

- “I’ve seen a change in how things happen. I’d say the pipeline from Capitol Hill has really changed this place for the worse.”

- “In the past, academics or lawyers were commissioners, and they were used to bargaining and seeing the nuances of both sides. This made deal making possible. Today, things have gotten way too political around here. It is sad to see the lost opportunities.”

To be sure, we do not think that the increasing prevalence of staffers-turned-commissioners generates uniformly negative consequences. Their familiarity with the legislative process may encourage greater care both in agency statutory interpretation and rulemaking. And their ties to elected officials may pull cloistered agencies more into the orbit of a democratically accountable branch.

Nonetheless, the notion that staffers-turned-commissioners import Congress’s pathologies to the administrative state should not be ignored. Good-faith deliberation is valued on multi-member commissions, and this quality is in short supply on Capitol Hill. As the White House and senators consider appointments to these bodies, this dynamic should give them pause.

Brian D. Feinstein is an Assistant Professor of Legal Studies & Business Ethics at The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.