D.C. Circuit Review – Reviewed: Disease

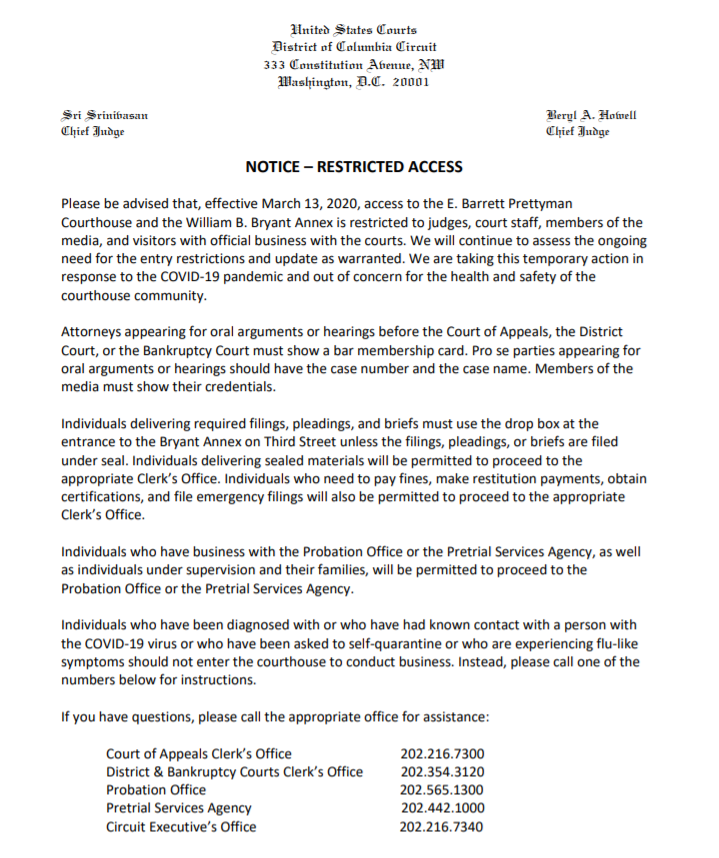

Well. This week took a turn I didn’t expect.* Which prompts a question: How has the D.C. Circuit handled disease? Here is the Court’s current approach:

And this:

But what about in the Court’s cases?

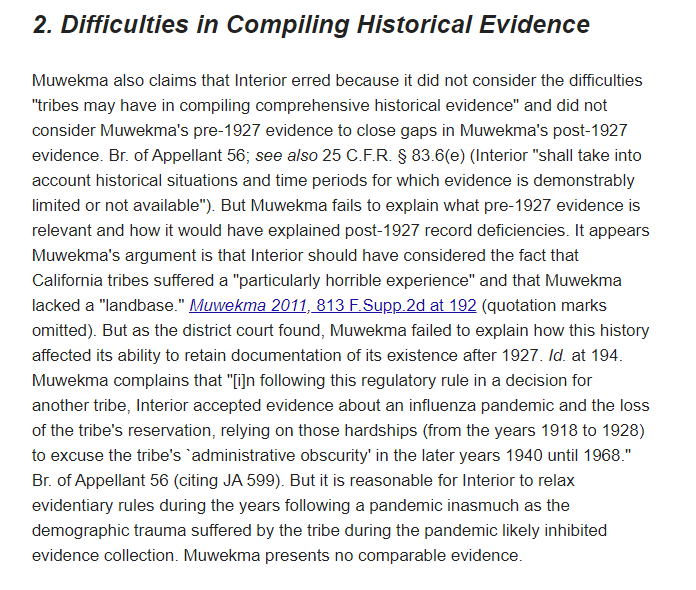

Surprisingly, the word “pandemic” has not been used very often. The most recent use was in 2013, in Muwekma Ohlone Tribe v. Salazar, which concerned recognition of a tribe:

Before that, the Court mentioned “pandemic” twice in the 1970s. The Court referred to “pandemic financial instability” and “television advertisements for sugared products [that] tend to promote unbalanced, over-sugared diets which have led to pandemic levels of tooth decay in this country.” That’s it.

The word “contagious” generates more hits, however. In 2010, for instance, the Court said this: “We have no doubt that OMB frequently produces documents that contain recommendations, but such documents are hardly contagious, spreading their predecisional and deliberative nature to all other documents in their vicinity.” That quote isn’t about disease, but it is intriguing. Likewise, in Miller v. Bond, the Court addressed the “extensive disruptions in air service [that] resulted as approximately one quarter of the nation’s air controllers reported in sick each day between March 24 and April 14, 1980.” And in American Medical Association v. United States, the Court confronted price-fixing in the medical community.

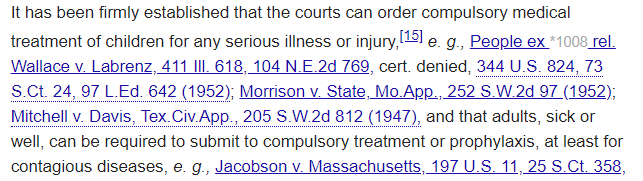

Sometimes, however, the Court really has addressed sickness. Consider Creekstone Farms Premium Beef v. Department of Agriculture, which involved test kits for Mad Cow disease. (On the subject of sick animals, the Court also has confronted sick giraffes and tortoises.) Likewise, in Application of President & Directors of Georgetown College, the Court stated as follows:

Moving further back in time, here is what Chief Judge Prettyman — that Prettyman — had to say:

See also:

- Loube v. District of Columbia, 92 F.2d 473 (D.C. Cir. 1937) (“The maintenance of public schools, fire departments, systems of sewers, parks, and public buildings, it has been definitely determined, calls for the exercise of a governmental function. Certainly the protection of the city from accumulations of garbage involves the exercise of a governmental function to almost as great an extent as the maintenance of a system of ‘public sewers so necessary to preserve health.’ ‘The accumulation of garbage, of substances offensive to the sense of smell, of substances which, if permitted to remain, would poison the atmosphere, and breed diseases infectious and contagious among the inhabitants of the city, may well be said to endanger the public health. The preservation of the public health involves the removal of those causes which are calculated to produce disease.”);

- Rule v. Geddes, 23 App. D.C. 31 (1904) (“There is a considerable class of cases which lies beyond the domain of usual litigation and the customary jurisdiction of the courts, and in this sphere it is found that due process of law, as generally understood, is subject to numerous exceptions and decided limitations. Thus the provision against restraint of liberty is generally held to have no application whatever in the cases of lunatics, infants, and some other classes of persons who need peculiar protection or special oversight in their own interest or in that of society. Persons, for example, suffering from contagious diseases may be imprisoned in quarantine without other process of law than the command of the health officer. It is likewise held in some courts that lunatics may be restrained of their liberty and committed to appropriate places of treatment without any legal process at all. A statute has been held valid which authorized overseers of the poor to commit to the workhouse persons leading a vagrant and dissolute life, and this on the ground that the purpose of such an enactment is not penal, but correctional and reformatory.”);

- Shoemaker v. Entwisle, 3 App. D.C. 252 (1894) (“Undoubtedly, there are cases where summary power may properly be vested for special purposes even in subordinate officials. The threatened spread of conflagration may justify the demolition of property in the probable pathway of the flames. It is proper to seek to prevent the threatened spread of contagious or infectious diseases by the destruction of infected clothing, and by quarantine regulations that sometimes very seriously interfere with the rights of personal liberty. There is no more dangerous thing to a populous or crowded city than insecure buildings or toppling walls; and it is proper that summary power to remove the danger should be vested in the public authorities, to be exercised through subordinate officials. Salus populi suprema lex—the public safety is the supreme law—is the maxim that governs in such cases; and it is not only the right, but it may be the duty, of those charged with the supervision of such matters to act promptly and summarily in the discharge of their official functions.”).

The past is not always a foreign country. Even so, it is usually an interesting place to visit.

###

The D.C. Circuit decided a slew of cases this week — big ones, too.

- Eagle Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Azar: This case is about disease, so let’s start with it. Judge Henderson — joined by Judge Rao — concluded that Eagle was entitled to marketing exclusivity for an “orphan drug” (that is, a drug that “is designed to treat a rare disease or condition that historically received little attention from pharmaceutical companies”) under the Orphan Drug Act. At bottom, this case is about what counts as ambiguity. Here is a sample: “The FDA is correct that the Congress did not specify whether the privilege of exclusive approval applies to one or multiple manufacturers but that fact does not create an ambiguity. If the text clearly requires a particular outcome, then the mere fact that it does so implicitly rather than expressly does not mean that it is ‘silent’ in the Chevron sense. Here, the particular outcome required by § 360cc(a) is that once a drug has been designated and approved, the FDA may not approve another ‘such drug’ for seven years—regardless whether that drug is the first, second or third drug to receive that benefit. The fact that the Congress chose not to include an additional requirement, limitation or exception for successive or subsequent exclusivity holders does not make the provision ambiguous.” Judge Williams dissented: “Because the majority’s interpretation of the statute runs counter to the best reading of the congressional language, and because it fundamentally upsets the basic economic bargain that Congress so carefully struck, I respectfully dissent.”

- Maryland v. Dickson: Judge Henderson — joined by Judges Tatel and Katsas — rejected Maryland’s request to vacate certain flight paths into Ronald Reagan National Airport. Maryland acknowledged that it filed its petition well past the 60-day review window, but it argued that it had reasonable grounds for delay. The Court disagreed.

- Chesapeake Climate Action Network v. EPA: Judge Wilkins — joined by Judges Tatel and Pillard — remanded a rule “establishing emission regulations under the Clean Air Act” because it was “impracticable” to comment during the notice-and-comment period. In particular, “[t]he Final Rule’s reliance on an identified list of best performing power plants was not a logical outgrowth of the 2013 Proposed Rule.” Paging Kristin Hickman and Richard Pierce: this case probably merits inclusion in your treatise.

- Evans v. BOP: Judge Sentelle — joined by Judges Millett and Katsas — confronted a federal prisoner who was stabbed from behind with a screwdriver in the prison dining hall. The Court held that the Bureau of Prisons had to turn over video.

- In re Al-Baluchi: Judge Tatel — joined by Judges Garland and Edwards — addressed “one of five co-defendants facing capital charges related to the planning of the September 11 attacks.” Here is the issue: “In defending against the capital charges, al Baluchi contends that his torture renders certain incriminating statements key to the government’s case inadmissible. According to al Baluchi, in order to make that defense, he needs evidence from one particular detention center, so-called ‘Site A,’ which the government plans to ‘decommission’—i.e., destroy—in the near future. He therefore seeks a writ of mandamus, asking us to prevent the government from proceeding with the site’s destruction. The government, however, has produced digital and photographic representations of Site A and al Baluchi cannot show, as he must, that it is clear and indisputable that those representations are so insufficient as to warrant the extraordinary remedy of mandamus.” According to Tatel, “substituting documentation for physical evidence is an accepted, even routine, evidentiary practice.”

- Irregulators v. FCC [note — great name]: Judge Williams — joined by Judges Rogers and Katsas — addressed an FCC “order approving the continued use of admittedly outdated accounting rules for an ever-dwindling number of telephone companies whose pricing is governed by those rules.” The challengers, however, lacked standing. Here is a sample: “For starters, none of the petitioners claims to purchase intrastate service from a rate-of-return carrier directly—hardly a surprise, given the reduced role of rate-of-return carriers. One petitioner states that he has traveled on business to every state in the Union except New Mexico and Alaska, and he has ‘consumed local telecommunications services’ while on the road. But he does not claim that he has paid for these local services directly, only that he has, like many travelers, used a phone while away from home.”

- Molock v. Whole Foods Market, Inc.: Judge Tatel — joined by Judge Garland — addressed a putative class of employees who allege Whole Foods manipulated an incentive-based bonus program. Whole Foods argued that the district court lacked personal jurisdiction over the claims of the nonresident putative class members. Yet, says the Court, putative class members are never parties to actions prior to class certification. Judge Silberman dissented. You should read it. Don’t believe me? Well, here is a taste: “The plaintiffs and an amicus contend that my conclusions would have a devastating impact on the viability of class actions. I think that prediction is vastly overstated.”

- Campaign Legal Center v. FEC: A per curiam panel — Judges Tatel, Garland, and Edwards — affirmed dismissal of “three administrative complaints alleging violations of the Federal Election Campaign Act’s disclosure requirements.” The issue involves “straw donors.” A deadlocked FEC declined to pursue the matter because “Commission precedent and regulations provided inadequate guidance regarding how § 30122 would be applied to closely held corporations and corporate LLCs.” The panel upheld the explanation as sufficient. It did not decide whether refusal to pursue complaints as a matter of prosecutorial discretion is reviewable. Judge Edwards wrote separately to challenge that argument. If you are interested in agency non-enforcement decisions, here is a place to start.

- Finally, last (by certainly not least) is In re Application of the Committee of the Judiciary: Judge Rogers — joined by Judge Griffith — affirmed that the House Judiciary Committee can access grand jury materials related to the Mueller Report. Judge Griffith wrote separately to state that this case does not involve a suit between the political branches and therefore does not pose a problem under Committee on the Judiciary v. McGahn. Judge Rao dissented with particular focus on the reasoning in McGahn. I suspect there will be another opportunity to write about this one. After all, as of a couple of hours ago, the Court has also now decided to rehear McGahn en banc!

And with that, remember to wash your hands and stop touching your face.

* I run BYU Law’s D.C. Semester. We’re in the process of getting our students home. Many thanks to our externship providers for being understanding. It’s been a busy 24 hours. Hence, this post isn’t as fulsome as I wanted. C’est la vie, I suppose.

D.C. Circuit Review – Reviewed is designed to help you keep track of the nation’s “second most important court” in just five minutes a week.